- Call: 0203 427 3507

- Email: innovation@clustre.net

COLLABORATION

‘A Recipe for Success’

Collaboration is hard-wired into human nature. The notion of collaboration always reminds me of that wonderful scene in ‘Witness’ where the Amish come together, pooling their skills and resources, for a barn raising. It’s a powerful image and, of course, it’s a metaphor; they’re not building a barn, they’re creating a community.

Collaboration is hard-wired into human nature. The notion of collaboration always reminds me of that wonderful scene in ‘Witness’ where the Amish come together, pooling their skills and resources, for a barn raising. It’s a powerful image and, of course, it’s a metaphor; they’re not building a barn, they’re creating a community.

Collaboration, not surprisingly, is a common term in the business world. It’s used to describe everything from an informal workshop to a joint venture. We instinctively know collaboration is a good thing. We’re all doing it and we’re convinced that everyone else is doing it too (better and more often than us).

Humans are social animals. We’re happier working together. We’re also more productive and more successful when we’re having fun. By collaborating on things that are important to us, we create the possibility of sharing a triumph – and that’s much more enjoyable than solitary success.

So collaboration is a good thing. But is this just too good to be true? We’ve all experienced the frustration of working with someone who’s ‘not on the same page’ and not all shared endeavours are productive or enjoyable. So what does it take to collaborate successfully?

I believe there are four key ingredients in the recipe for a successful collaboration:

Commonality of Purpose

In order for any partnership or joint venture to be successful, the parties involved must have a genuine and reasonably long-term commonality of purpose. Sometimes our short-term goals can appear to be aligned but if we lack a genuine, enduring, common purpose our collaboration is unlikely to be successful.

For example, I’ve seen many instances where a client and a supplier have tried to build the business case for ‘productising’ a solution and then selling it to third parties to recoup costs and make a profit. This almost never works. Why? Because the client’s primary goal is to get the supplier to part-fund the solution; whereas the supplier’s primary goal is to create an attractive business case. Neither party is focusing on the long-term commercial success of the joint-venture as their priority.

There are exceptions. For example, in 1993, Accenture entered into a joint-venture with an airline to develop a unique system for Passenger Revenue Accounting. Over twenty years later, it is still going strong – only now it has more than 50 worldwide clients. The reason for its success is simple: right from the outset, the venture was conceived as a long-term service provider – both parties had a genuine common-purpose and commitment.

Another example of the need for long-term commonality of purpose can be seen in the poor track record of mergers and acquisitions in delivering sustained share-holder value. All too often the parties involved, egged on by their investment banking advisors, become fixated on the short-term goal of getting the deal done. They share this short-term objective, but the longer-term purpose gets lost in the adrenalin of the deal. Think AOL/Time Warner.

Another example of the need for long-term commonality of purpose can be seen in the poor track record of mergers and acquisitions in delivering sustained share-holder value. All too often the parties involved, egged on by their investment banking advisors, become fixated on the short-term goal of getting the deal done. They share this short-term objective, but the longer-term purpose gets lost in the adrenalin of the deal. Think AOL/Time Warner.

In contrast, the most successful collaborations are those where the parties come together to pool their skills and resources to achieve a common purpose. I think perhaps my favourite example is between independent race-car constructor Carol Shelby and the Ford Motor Company. This collaboration had the single-minded objective of beating Ferrari at Le Mans and culminated in the stunning Ford GT40 winning Le Mans in four consecutive years (1966 to 1969). The story of this epic battle between Ford and Ferrari and the crucial role played by the maverick Shelby is the stuff of legend.

Complementary Skills and Experience

On one level, the whole point of collaboration is to pool our skills and experience. This clearly works best when our skills and experiences are not just compatible but – more crucially – complementary.

Whenever we start something new, something we have never done before, we enter the realm of unconscious incompetence… we don’t even know what we don’t know! Almost anyone who develops a new idea or tries to launch a new business falls into the same trap: focusing too much on the things they’re good at… not enough on the things they’re not good at… and not at all on those things they don’t even know they need to be doing. Let me explain…

Most innovators are product-centric. They have a great idea for a new product, process or service. They then pour all of their energy and creativity into developing and perfecting their ‘baby’. They are fully aware of the importance of marketing and attracting customers, but it isn’t their prime area of expertise and it’s not what they enjoy doing. So it’s side-lined. And curiously, they often compound this weakness by seeking a partner or co-founder with similar technical or product skills rather someone with brand development experience or a sales & marketing background.

Most innovators are product-centric. They have a great idea for a new product, process or service. They then pour all of their energy and creativity into developing and perfecting their ‘baby’. They are fully aware of the importance of marketing and attracting customers, but it isn’t their prime area of expertise and it’s not what they enjoy doing. So it’s side-lined. And curiously, they often compound this weakness by seeking a partner or co-founder with similar technical or product skills rather someone with brand development experience or a sales & marketing background.

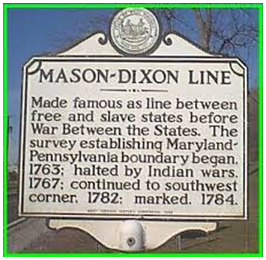

By contrast, the most successful collaborations are often between people with very different backgrounds and expertise. By collaborating with people ‘not in our own image’ we create the possibility of learning from someone with a completely different point-of-view. Take for example the collaboration between Mason and Dixon.

Charles Mason was an astronomer from the Royal Greenwich Observatory in London; Jeremiah Dixon was a surveyor from County Durham. Together, using Mason’s navigational skills and Dixon’s experience as a surveyor, they plotted the Mason-Dixon Line which defined the State boundaries between Maryland, Pennsylvania and Delaware. In the process, they not only resolved a border dispute they also wrote an important chapter in American history.

Creatively Compatible Personalities

I recently made the mistake of bringing together two alpha-male executives who, on paper, had complementary skill sets. They were each coming at the same problem from different perspectives. It seemed to me that neither had everything they needed to succeed by themselves but together they could be a formidable team. But, from the moment we sat down together, it was clear the chemistry was never going to work. Neither party felt they were getting the respect they deserved. Neither valued sufficiently the skills and experience of the other party. Perhaps more importantly, their creative styles were very different.

In stark contrast, I recently worked on a large outsourcing deal where the client executive and sales lead had worked together for many years and closed several large deals. Their shared understanding of the deal process and the way they worked together was highly collaborative and, although very different characters, the personal chemistry worked very well. There was a level of mutual understanding, trust and respect that carried them through the difficult parts of the negotiation, even when there was disagreement.

Most strikingly, when faced with a seeming impasse in negotiations, they worked together creatively to find a solution.

The whole point of collaboration is to come together to create something. It’s often the associated creative tension that makes or breaks a collaborative relationship. So I always think a good test of compatibility is whether you are able to feed off each other’s creativity.

I think this is why so many great collaborations have been in the arts: Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro; Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel; Sergio Leone and Ennio Morricone (I know I’m showing my age).

Similarly, in the business world, the most successful collaborations are essentially creative in nature. For example, the relationship between Jony Ives and Steve Jobs was perhaps the most successful collaboration in recent times.

Sense of Fair Play

I’d like to finish by touching briefly on one last (but often overlooked) ingredient in the recipe for successful collaboration: a sense of fair play. In any collaboration the stakeholders each bring different things to the party and they each benefit in different ways from the results of the collaboration.

I’d like to finish by touching briefly on one last (but often overlooked) ingredient in the recipe for successful collaboration: a sense of fair play. In any collaboration the stakeholders each bring different things to the party and they each benefit in different ways from the results of the collaboration.

You may recall the tale of the hen and the pig. The hen approached the pig with a great idea for a new business venture. The hen’s idea was to set up a stall to provide breakfast each morning as the workers arrived at the farm.

“I’ll provide the eggs,” said the hen, “and you provide the bacon.”

The problem of course is the pig’s resources are far more valuable to the pig than the hen’s are to the hen. It would be almost impossible to devise a split of the profits that would reflect the relative value of each party’s contribution. The pig would, quite literally, be giving his all.

I see this time and again in the business world. Two parties coming together to collaborate but failing to come to terms because their view is too narrow and subjective. They measure each other’s participation in terms of the value contributed to the end solution… it rarely occurs to them to consider what it will cost the other party to participate.

An ability to stand in each other’s shoes and a sense of fair play are essential. So next time you are entering a collaborative relationship, my advice is to try to see things from the other party’s point-of-view and genuinely strive for fairness. Ask yourself objectively if the benefits your collaborator will get from working with you will be sufficient, in their eyes, to make it worthwhile.

Thank you for collaborating

These are my four key ingredients for successful collaboration. In the spirit of this article I’m sure this recipe can be improved by pooling our experiences. So, if you have other ingredients that you consider to be critical to the perfect collaboration, please let me know.

In the meantime, let me invite you to share some more insights…

If you would like to know how one of our member firms helped a global giant to stay connected with its own people, do listen to our latest podcast. Sherry Rafiq – Head of communications at Vodafone – shares her experience on how to make social collaboration a reality in the workplace.

Andrew Simmonds is Consulting Director at Clustre – The Innovation Brokers www.clustre.net