- Call: 0203 427 3507

- Email: innovation@clustre.net

Experiments are the best way to answer fundamental business questions and get closer to customer needs. Why don’t more companies use this simple approach?

How do we drive value more quickly?” asks Richard Cross, CDO of Atkins, “How do we not spend months thinking, but develop something quickly, experiment and improve?”

It’s a very common question. Fluxx are often asked to help organisations validate ideas with experiments. Sometimes the ideas and experiments are huge: operating a pet startup for six months; creating a new type of payment card. Often they’re simple and quick.

People at the top of big organisations are constantly asked to judge and prioritise ideas: features, brand extensions or new products. Often they’re reactions to new technology or a disruptive startup. Something fundamental has shifted in the business, demanding an urgent response.

Leaders have to make judgements before anything has been built.

Ideas arrive as a pitch; a powerpoint deck selling a dream accompanied by a spreadsheet filled with hopeful numbers.

In some organisations, ideas live as pitches for years. The lucky ones become projects. Budgets are attached, staff are hired, Gantt charts are drawn. Eventually, the product is launched and exposed to the real world for the first time.

Sometimes, this is a shock.

Supply chains are fragile and details get missed. When this happens, a new idea is born. A new way to fix the old idea, with more powerpoints, spreadsheets and Gantt charts. It’s exhausting, and expensive. Some of the Fluxx team have been there many times in previous jobs.

There is another way to work. A way to unlock the potential in an organisation, and release the ideas and talent and ambition of your team.

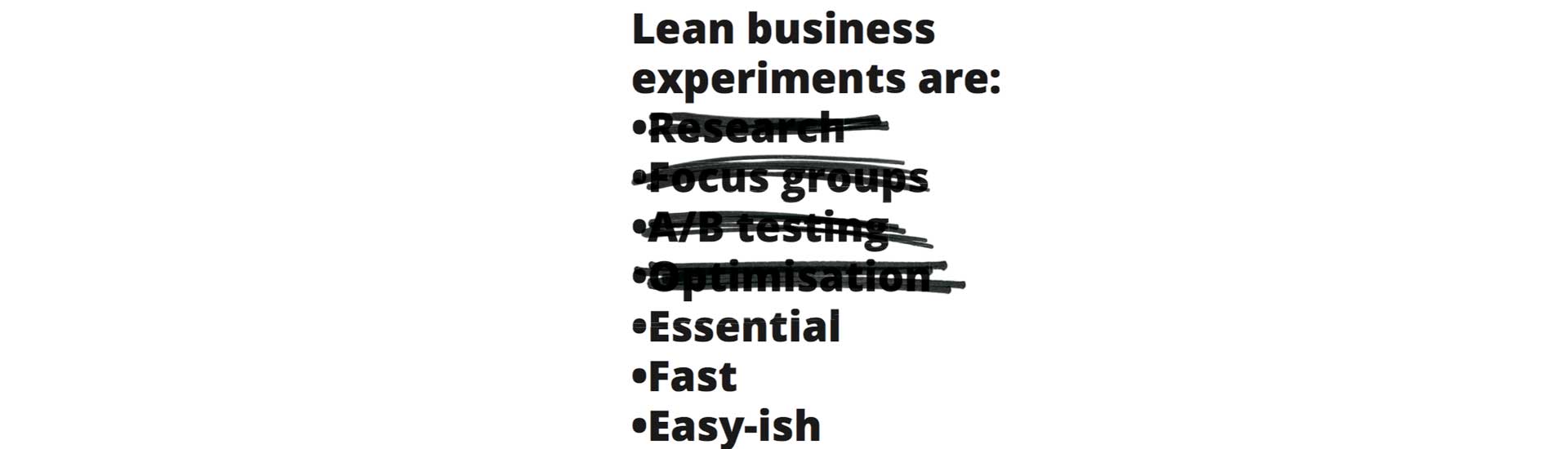

We learned the idea of lean business experiments from startups. Someone bootstrapping an idea from their kitchen table can’t afford to waste time or money on ideas that are unlikely to succeed.

So the best-run startups run experiments to test their ideas with real customers.

This helps them discover which new ideas are likely to succeed in their market. Experiments generate real evidence, so investment decisions can be made with more confidence. They reveal problems before they’re baked into the product.

Critically, they replace opinions with facts, and they do it quickly. All of this reduces the risk and uncertainty associated with new ideas and technology.

CEO Travis Kalanick grins when he tells the story: “In the beginning, it was a lifestyle company. You push a button and a black car comes up. Who’s the baller? It was a baller move to get a black car to arrive in 8 minutes.”

It wasn’t real. It wasn’t scalable, sustainable, or profitable, but it was desirable. People desired a magic button to summon a black limo. And investors flooded in to make their dream a reality.

Uber is still an experiment. They’ve proved that the service is desirable and feasible, but by losing $1bn a year, they’ve not yet proved it is viable.

Leaders must replace their bluster and infallibility with trust in the process. Eric Ries, the journalist who popularised the lean startup, says “‘If you cannot fail, you cannot learn.”

Bookmakers William Hill had wanted to develop a winnings card for some time, to let online customers spend their winnings immediately. The idea was big, innovative and promising, but had stalled because fundamental questions remained unanswered: how would customers

react? What impact would the card have on their spending habits?

It was hard to justify the huge investment required without answers to these questions, and hard to find answers without the huge investment.

Over just two days Fluxx helped the William Hill team to launch a real winnings card for 20 customers.

For those customers, it was a slick and useful service. Behind the scenes it was a little more hand-cranked, with pre-paid Mastercards and a back room team in the Phillipines using a lashed-together system to reconcile the accounts.

The experiment ran for 90 days, giving William Hill a deep understanding of how customers used and perceived the card. The insight helped them incubate and launch the Priority Access Card in March 2016, winning a slew of industry innovation awards.

Launching an experiment creates a real, living, new product or service. At the end, you don’t just have a PowerPoint deck. You have customers, a team, business processes and perhaps even revenue.

The Wagglepets stock room at our fulfillment partner’s warehouse in Bristol

“My dog only eats cheese treats,” said the customer on the phone. She’d just received her first monthly box from Wagglepets, a startup that Fluxx launched with More Than, the insurance company, and she wasn’t completely happy.

The challenge from More Than was to reinvent pet insurance. Instead of being a tax on life, could we turn it into an attractive lifestyle product?

We ran Wagglepets for six months, recruiting 40 customers. It was radically different from a market research project. We saw how customers really reacted to our product, rather than just getting answers to hypothetical questions.

Actionable insights flooded out of the process. We planned to sell one brand of dogfood, but ended up with ten. We quickly abandoned Fitbit-style fitness trackers because customers hated the connection with insurance.

Our experiment validated our hypothesis: people would pay for a bundle including food, toys and insurance, and we learnt how to operate the business. By 2017 the experiment was a success, and More Than took the product mainstream under the Doggysentials brand.

Running experiments teaches a novel collection of skills, from a robust understanding of the regulatory and legal context to an intuitive sympathy with customers, ensuring they never feel cheated or manipulated by the experiment.

The Zume call centre, where we managed a transport system in Cambridge from the Fluxx office in Clerkenwell

The first step in designing an experiment is to break the idea into assumptions. What beliefs have to be true for the idea to succeed? Test the assumptions that are both risky and crucial to the idea’s success.

During a ‘Name Your Price’ project with RSA Insurance, the most important and risky assumption was that people would suggest reasonable prices when asked. We created a disposable brand and built a simple web page: a video explaining the offer and a form to send us a price.

We ran ads on Google for a week. The test confirmed our hypotheses — people had named their price, and the range of prices were reasonable.

Another example: For an Intelligent Mobility project with Atkins, we needed to learn how commuters would use a high-tech transport system that hasn’t been built. So minicabs stood in for autonomous taxis and busses. Fluxx staffers with bundles of tickets stood in for unified billing systems. We took passengers on 118 trips during November 2016, gaining unique insights into their expectations and reactions.

Running experiments can be scary and fun and unsettling; but they are the best way we know to get from idea to real transformation without wasting time or money.

To learn more about Fluxx and lean experiments, or to get an invite to our monthly experiment meetups email Richard Poole: richard.poole@fluxx.uk.com