- Call: 0203 427 3507

- Email: innovation@clustre.net

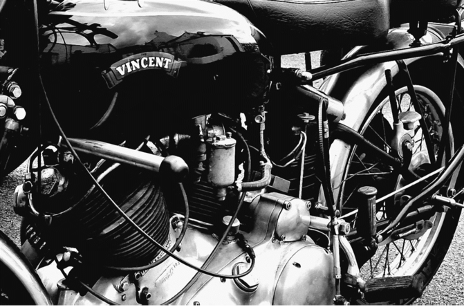

Disruptive innovation is not a new phenomenon. Back in the ‘Swinging 60s’, Britain’s motorcycle industry was hitting the skids. In 1969, on the verge of financial collapse, the MCCIA – the body representing the nation’s motorcycle and cycle manufacturing industry – submitted a report to the government. In painful detail, it listed the reasons why our once proud and world-dominant industry had taken a savage battering from foreign competition.

High taxation… over-regulation… artificial fiscal barriers… unfair subsidies for rivals by foreign governments… it was a depressing story of an unwinnable battle for survival.

But it was also largely untrue.

The real reason for the collapse of our motorcycle industry was revealed, six years later, in an independent report commissioned by the British Government. It makes very uncomfortable reading.

The Boston Consulting Group’s report – ‘Strategy Alternatives for the British Motorcycle Industry’ – was highly critical. ‘A concern for short-term profitability’ had, it concluded, eroded the industry’s pre-eminent position and left it vulnerable, at every level, to attack.

This pursuit of profit had robbed our industry of R&D funding. While Japanese and Italian rivals were investing in radical new products and high-tech manufacturing plants, Britain’s designers were raiding the parts bin for obsolete components and working in antiquated factories. It was a clash of cultures: Kaizen versus Complacency. The search for constant improvement versus an uncritical satisfaction with past achievements.

And these differences were manifest.

Many British motorbikes suffered from unacceptable engine vibration… they still used kick starters when competitors fitted electric ones… engines invariably leaked oil because of poorly fitting gaskets… engine castings were quite often porous… electrical components regularly failed where rival machines proved consistently reliable. On quality, handling, styling, ride comfort, reliability, engineering, value and performance, foreign machines were superior in every respect.

But the report’s most damning criticism was levelled at management’s strategy of ‘Segment Retreat’…

Initially, Japanese manufacturers focused their efforts on the entry-level, sub-250cc market. Honda, Suzuki, Yamaha (and others) perfected techniques of extracting previously unseen performance from very small capacity engines. Then they concentrated on mass-producing durable, quality bikes for a budget price. And blew their British rivals off the road.

This invasion should have been a wake-up call but our management barely blinked. They were content to let these newcomers nibble at the low-margin, low-hanging fruit because Britannia ruled the prestigious and profitable ‘bigger bike’ segments.

And they still believed this when, less than two years later, the Japanese moved into the 350cc segment… and ate their lunch. Again. Apart from a few raised eyebrows, management still couldn’t – or wouldn’t – see the threat.

Deluded and in denial, we retreated as the Japanese advanced into the 500cc and ultimately into the Superbike sector. Finally, the British motorcycle industry had nowhere left to retreat. It had been comprehensively outperformed on every level.

This collapse is brought into stark perspective by one statistic. At the start of the 60s, Britain supplied the world. We were the greatest and most respected force in motorbike production. By 1974/75, despite major restructuring and repeated government hand-outs, we struggled to manufacture just 20,000 motorbikes. In the same single year, one Japanese company – Honda – made over 2,000,000.

This sad demise is a classic example of disruptive innovation. A bold assault on a core industry that had grown smug, complacent, myopic, and excessively greedy. But this litany of failure is not confined to motorcycles. Our industrial landscape is littered with companies that have been picked off and devoured by alpha predators. And one of the biggest car crashes was Britain’s motor industry…

The late 70s, 80s and 90s were a feeding frenzy. A toxic mix of feuding management, hostile unions, woeful products, and intense competition triggered a catastrophic collapse in our car industry. All of Britain’s most historic and prestigious marques were snapped up by foreign companies – predominantly BMW, VW and Tata.

It’s not much of an epitaph. But it is a red flag. A management alarm call. In a world where disruption and change are the only status quo, we are left with one brutal, binary choice. Seize the initiative or suffer the consequences. Because without visionary leaders, investment and, above all, innovation, British industry is plump, easy prey.

This article first appeared in ‘Innovation without Fear’ – our first management book. It explains Why, Where and How to drive business-changing ideas in our deeply challenged world, You can obtain your own copy by clicking this Amazon link: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Innovation-Without-Fear-liberate-business-changing-ebook/dp/B09T5R61Z1